How a Blog Post Became SkiFree, a Music Engine, and 356 Claude Code Sessions

Feb 9, 2026 · 6 min read

I was trying to build a procedural music engine in Web Audio API. Everything Claude gave me sounded like a ringtone. I kept prompting “make it better,” “add more depth,” “make it more emotional.” Six words that produce absolutely nothing, every time.

Then I wrote this: “Think about the upgrade from NES to SNES. Less gameboy, more super famicom. Think donkey kong country samples, the depth of a JRPG soundtrack, the epic surreal beauty of a PC-98 game.”

Night and day. Same engine, same code structure, completely different output.

That moment, about four days into a ten-day build, changed how I prompt for everything. This post is the story of what I was building when I figured that out, and the five prompting lessons I walked away with after 356 Claude Code sessions and 280 commits. If you use AI to build anything creative or complex, I think these will save you a lot of the time I wasted learning them.

The Project That Ate My Week

It was supposed to be a blog post. Seven chapters explaining agentic coding to PMs and CEOs. A few Win95 window frames for personality. Maybe some checklists. One commit on January 31st: “Add interactive guide.”

Then I added interactive window control buttons (minimize, maximize, close) and something clicked. The theming wasn’t decoration. It was the product. By midnight I had an FFVI-style pixel art wizard, per-chapter illustrations, a salary calculator, and a dock with colored icons. Twenty commits on day one.

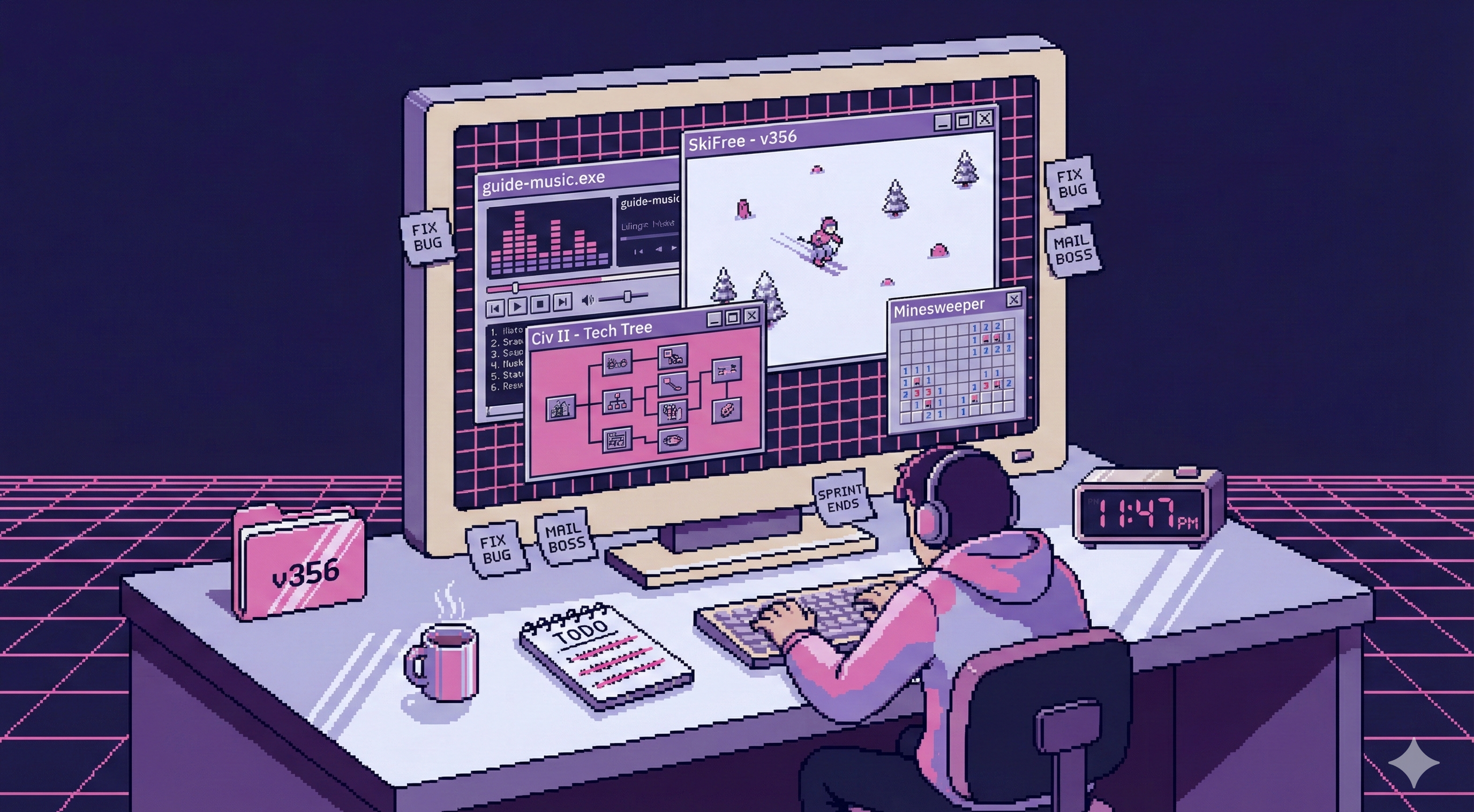

Ten days later: a playable canvas SkiFree, a procedural music synthesizer, a Civ II tech tree with curved SVG dependency lines, a working disk defragmenter, a Minesweeper minefield, a SimCity budget advisor whose pixel-art face changes mood based on your numbers. Around 16,000 lines of code across 23 files. Here’s the finished thing.

I didn’t plan any of this. Each feature created a gap that the next feature filled. The Win95 chrome needed a mascot. The mascot needed to react to your progress. The progress tracker needed a visual payoff. Scope creep, but the productive kind, where you can feel the thing getting better with every addition.

The interesting part isn’t the features though. It’s what I learned about working with AI across 356 sessions of creative and structural work in the same project.

Lesson 1: A Proper Noun Beats an Adjective. Every Time.

Back to the music engine. After the Donkey Kong Country prompt worked, I kept testing the pattern. I asked “Nobuo Uematsu, how can we make this piece from great to timeless classic?” Then I had Claude roleplay as the best Super Famicom composers of all time and critique the composition. Sounds absurd. Produced the best iteration of six rewrites.

The music went through a Shimomura-style melody, a Philip Glass arpeggio, an Uematsu phase, an SNES/PC-98 hybrid, a “Soulful Mix with Sound Canvas vibes,” and finally full dembow with karaoke lyrics because the guide needed energy. The final module is 2,400 lines of Web Audio API, zero samples, everything synthesized. Three commits just to get AudioContext unlocking right on mobile Safari.

The pattern held everywhere, not just music:

- “Make it more premium” produced nothing. “Win95 beveled borders, not flat design” produced exactly what I needed.

- “Improve the typography” went nowhere. “Have a master typesetter work on the hero section” got me real improvements.

- “Make the design better” was useless. “Check out poolsuite.net and come up with ideas from there” gave me concrete inspiration.

The rule: name the reference. A specific game, a specific composer, a specific website, a specific feeling. “Elegant” means nothing to an LLM. “The feeling of hearing Corridors of Time for the first time” means something. Adjectives describe a region. Proper nouns describe a point. You want the point.

Lesson 2: Vibe for Creative Work, Blueprint for Structural Work

For creative tasks (music, game feel, UI theming, copy), short emotional nudges worked. “Can you make this sound more boricua? Add cuatro somewhere.” Under 15 words, mid-session, trusting the shared context. The persona prompting from Lesson 1 lived here too. “Have a master UI/UX designer from Apple that worked for YCombinator take a stab at this” produced better design feedback than any description I could write.

For structural tasks (refactoring a 4,378-line SCSS file into seven, standardizing spacing tokens across 23 files, responsive layout fixes), the opposite worked. I’d write a full plan first, then paste it as “Implement the following plan:” with file paths, exact values, and explicit instructions.

I wasted real hours before noticing this split. Vibing on a refactor gives you inconsistency. Different spacing values in every file, different naming conventions, no coherent system. Blueprinting a creative task gives you generic. Safe, competent, lifeless.

The same AI, the same session, completely different prompting styles depending on whether the task needs exploration or precision.

Lesson 3: Talk First, Prompt Second

The guide originally read like polished AI marketing copy. Every section was competent and completely lifeless. I tried rewriting the prompts, adding personality instructions, asking for “Gabe’s voice.” Nothing worked. You can’t describe your way into sounding human.

So I tried something different. I had Claude generate a long interview about my career, my failures, the projects I’d shipped. Then I answered those questions in Spanish via voice memo. Just talking. Rambling about graduating from Colegio de Mayaguez, the two years at Georgia Tech, building Peer Feedback for the campus and watching over a thousand students use it, the CITYROW acquisition where I had to step up as the technical leader when everything was falling apart.

I fed the transcription back and told Claude to weave those stories into the guide as personal notes.

The result sounds like me because it is me. The AI shaped and placed the stories, but the raw material was my actual voice talking about things I actually care about. Record yourself talking in whatever language is most natural to you, transcribe it, and let the AI edit. Don’t let it write from scratch. This is the single fastest way to get content that doesn’t sound like AI.

Lesson 4: Show, Don’t Describe

Half my prompts during the build were a screenshot and three words. “Fix this on mobile.” “This still happens.” I used a Playwright browser plugin that lets Claude see the site, take snapshots, and interact with elements.

Describing a CSS bug in English: slow, ambiguous, misunderstood on the first try. Showing it: instant. This isn’t a minor workflow optimization. Visual context carries information that would take a paragraph to describe and still miss something. A screenshot of a button overlapping a card on iPhone is worth more than “the button positioning seems off on smaller viewports.”

Lesson 5: Let AI Brainstorm, Then Be Decisive

None of the game metaphors were planned in advance. My flow for every chapter was the same: “come up with ways to make this more interactive and fun,” get a numbered list, pick one.

“1. lets go for 1… this is epic” is literally how the Minesweeper theme happened for the common mistakes chapter. The Civ tech tree started with “what about something out of Civilization 2 or 3?” The defragmenter came from asking how to make the codebase readiness checklist less boring. SkiFree was the only one I walked in knowing I wanted, because pressing F to outrun the yeti was the perfect metaphor for the chapter’s point.

Claude brainstorms well. Better than I expected. The trick is being decisive about which idea to pursue instead of asking it to refine all of them. Pick a number. Say go. Iterate on the one thing.

What I’d Do Differently

Two things.

First: start with the interactive concepts, not the prose. Every chapter got better once I figured out its game metaphor. The Minesweeper theme made the common mistakes chapter fun to read. The Civ tech tree made the 90-day plan tangible. The defragmenter made the checklist feel like progress instead of homework. The writing shaped itself around the interaction, not the other way around. The static chapters that never got a game are noticeably weaker.

Second: commit to scope creep early or don’t do it at all. The middle ground, where you keep telling yourself “just one more feature,” is where the real time goes. I should have decided on day one that this was going to be a full interactive experience and planned accordingly. The 4,378-line single SCSS file I eventually had to split into seven? That happened because I kept adding “just one more thing” without stepping back to reorganize.

356 sessions in ten days. The project turned into something I couldn’t have built at this scale without AI-assisted development. The irony of building a guide about agentic coding using agentic coding was not lost on me. But the real takeaway is simpler than any of the features: stop describing what you want. Name it instead.